26

2025

From Fit to Contribution: My First CHI by Yuhao Sun

When I walked into the Pacifico Yokohama for CHI ‘25, I reminded myself of one thing: no need to try to absorb everything – just be present.

This was my first CHI – and perhaps more importantly, it was my first real test of how I – as a researcher situated between health / precision medicine, computing, and design – could find my place in an ever-expanding and ever-evolving academic HCI community.

Precision medicine, but for whom?

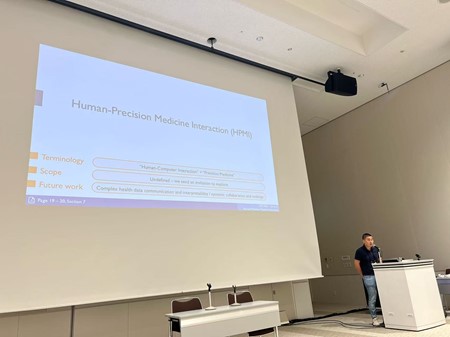

At CHI, I presented my work on Human-Precision Medicine Interaction – continuing a thread I had begun at DIS ‘24. As a part of my PhD, this paper explores how people relate to polygenic risk scores (PRS), an emerging genetic-based health prediction technology. Presenting it felt less like introducing a new topic to HCI and more like testing whether this conversation could be sustained – and how it will be perceived by other colleagues at CHI.

No one questioned its relevance directly, but a panel titled The Churns and Turns of HCI offered an indirect prompt: What makes a paper impactful? The answers were about timing, networks, and visibility. It made me pause. Was my work reaching the people who might shape where it goes next? The challenge wasn’t whether PRS or precision medicine ‘fits’ in HCI, but whether I had done enough to connect. Not just to the communities I came from, but to ones I hoped to grow with. The work may live between worlds, but impact comes from building threads strong enough for others to follow. It also made me wonder: how might the genetics community see this work?

Positioning between design and health

I attended DIS ‘24 last year as a doctoral consortium participant. It was one of the first times I felt part of a community that approached health not just as a problem to solve, but as a space for creative exploration. The work at DIS was experimental. I could feel that I was encouraged to try new forms of expression. It felt like a place where I could take risks.

At CHI ‘25, I joined the Interactive Health workshop – the first SIGCHI-sponsored Interactive Health conference will be held in 2026 (congrats!), and we were to envision the possibilities of it at the workshop. The focus there was different. The conversations were more grounded in evidence, methods, and impact. We talked about evaluation, about practical relevance, about contributing to real health practices. It made me pause and think again. Creativity is important, but it also matters whether what we make can be used, understood, or taken further by people in the wider field of healthcare.

I tried to compare the two communities – DIS health and CHI health. I wondered which direction I should follow. But I realised I want to pursue both. Both are necessary. I’ve had the honour of peer reviewing work by colleagues at both CHI and DIS. And I found some health research at DIS may not clearly show its impact on health systems. Sometimes it doesn’t even aim to. But that doesn’t mean it has less value than CHI’s. In fact, it shows something important: that some health HCI research needs to begin with design, even if the outcomes are uncertain.

Still, I can’t ignore the risk of pilotitis – of staying in the early stages and never building enough to make a difference. This is something I now take more seriously. Whether at DIS or CHI, doing health HCI means asking ourselves hard questions: Is this work de facto situated in health in a meaningful way? Could it ever be picked up by those working in care, policy, or practice?

Being present in the crowd

Something different from DIS ‘24 was – CHI ‘25 had over 5,000 attendees. Wow. On the first day, when I saw the coffee break line stretching like the Great Wall, I froze for a moment – I would never have enough time or energy to talk deeply with everyone I was interested in connecting with! It felt oddly personal. I wasn’t just navigating a conference. I was navigating my own expectations.

So I let go of the idea of covering everything. Instead, I focused on being intentional. I stopped chasing every ‘important’ person / talk and started noticing who I naturally connected with – someone I kept bumping into at sessions or someone whose question during a panel mirrored my own thinking. I started asking some different questions, not just “What do you work on?” but “What brought you here?” or “What are you trying to figure out right now?”

I learned not to feel guilty for taking time alone. I walked around Yokohama’s harbour, had ramen (and I went to two ramen museums and three ramen stores), and sat quietly by the water. It helped me stay calm and curious. Burnout doesn’t always come from doing too much. Sometimes it comes from trying too hard to prove you’re making the most of it.

In the end, I didn’t talk to everyone. I didn’t attend all the social events I was interested in, either. But I left with conversations I want to continue – and that felt like enough.

A ‘quiet’ realisation

Masako Wakamiya 若宮 正子, a 90-year-old Japanese app developer, gave the closing keynote. She started coding in her later life. Her story was quiet but powerful. A reminder that relevance doesn’t always come from scale or speed. It made me think about how often research is driven by pressure – publish, perform, produce. But there’s also value in choosing to work on something simply because it matters to you. Longevity, in that sense, might come less from visibility and more from staying curious. Years from now, will I still be drawn to questions that feel urgent only in the moment? Or the ones that continue to feel worth asking?

CHI didn’t give me all the answers. But it did give me better questions – and people I want to ask them with. The most valuable takeaway wasn’t a new method or paper. It was a quiet realisation: research is not about proving your worth but discovering where you can be of worth to others. From validation to contribution – the shift here might be the most important thing I bring back from Yokohama and my first CHI.